| William W. Coventry | home |

| Table of Contents | Introduction | A Sample Case: The Trial at Bury St. Edmunds | Other On-Line Book Sellers | Contact the Author | Witchcraft Links |

| A Sample Case: The Trial at Bury St. Edmunds |

| (chapter 5) |

|

After examining the numerous ways people interpreted or manipulated possession cases in the previous three chapters, it is important to view the state of affairs a half century later. After the political and religious machinations of the John Darrell and Mary Glover trials, the sordid fraud of the Anne Gunter case, and the increasing skepticism of King James I, it would be understandable to believe possession trials would soon die out. Unfortunately, possession cases and witchcraft trials continued to occur sporadically throughout the century.

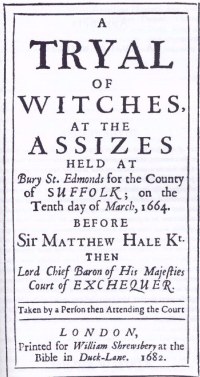

A three-day trial occurred at Bury St. Edmunds from March 10-13, 1662, which provides us with an interesting possession case quite free from the political coercion, religious rivalries, and the nefarious schemes of other trials we have examined. All we know about the trial is from a sixty-page pamphlet entitled A Tryal of Witches, at the Assizes held at Bury St. Edmonds for the County of Suffolk; on the Tenth day of March 1664 (though it actually occurred in 1662). Published in London in 1682, supposedly by an anonymous spectator, this pamphlet is the sole primary source for the trial.

Though the trial occurred at Bury St. Edmunds, the events leading up to it occurred in Lowestoft, an isolated fishing town with a population of about fifteen hundred one hundred and twelve miles northeast of London and fifty miles east of Bury St. Edmunds. At the time of the trial, Lowestoft was involved with a lawsuit against the larger fishing town of Great Yarmouth over fishing rights, which involved two principal members of the witchcraft trial, Samuel Pacy and Sir Matthew Hale.

Like many witchcraft trials, the incident that initiated the trial at Bury St. Edmunds transpired when a reasonably prosperous member of the community denied a request from a poorer one. In this instance, Samuel Pacy, a wealthy fish merchant and property owner of Lowestoft, rejected several requests from Amy Denny, a widow with a reputation as a witch, to sell her some fish. According to Samuel Pacy, whose deposition is recorded in the 1682 pamphlet, immediately after he turned down Amy Denny a third time, his daughter, Deborah “…was taken with most violent fits, feeling most extream pain in her Stomach, like the pricking of Pins, and Shreeking out in a most dreadful manner like unto a Whelp, and not like unto a sensible Creature.”

After Deborah's symptoms continued for three weeks, Pacy asked a neighbor, Dr. Feavor, for his opinion, but Feavor could not diagnose a natural cause of the illness. Though Pacy consulted a doctor, it appears he did not seek the help of the clergy, which presents a unique absence in demonic possession trials. Nor in Pacy's deposition at the trial is there any mention of employing any religious methods of dispossession.

Samuel Pacy's deposition stated that Deborah Pacy, “… in her fits would cry out of Amy Duny as the cause of her Malady, and that she did affright her with Apparitions of her Person.” After Samuel Pacy made a formal complaint, the authorities put Amy Denny in the stocks on October 28. This, however, did not end his daughter's symptoms. According to the pamphlet, two days later “…being the Thirtieth of October, the eldest Daughter Elizabeth, fell into extream fits, insomuch, that they could not open her Mouth to give her breath, to preserve her Life without the help of a Tap which they were enforced to use…”

For the next two months, the two sisters suffered other symptoms, including lameness and soreness, loss of their sense of speech, sight, and hearing, sometimes for days. Fits ensued upon hearing the words “Lord,” “Jesus” and “Christ.” They also claimed that Rose Cullender, another reputed witch, and Amy Denny, “…would appear before them, holding their Fists at them, threatning, That if they related either what they saw or heard, that they would Torment them Ten times more than ever they did before.” The sisters also coughed up pins, “…and one time a Two-penny Nail with a very broad head, which Pins (amounting to Forty or more) together with the Two-penny Nail were produced in Court, with the affirmation of the said Deponent, that he was present when the said Nail was Vomited up, and also most of the Pins.” Allotriophagy, the vomiting of extraordinary objects, provided an observable proof of possession.

As the Throckmorton family at nearby Warboys had done seventy years earlier, the parents relocated the sisters to the homes of relatives seven weeks after the initial illness in hope of a cure on November 30, 1661. While the girls lived at Margaret Arnold's house, their aunt who believed they might be faking their symptoms, she subjected them to an experiment. She removed all the pins from the children's clothes, yet, “…notwithstanding all this care and circumspection of hers, the Children afterwards raised at several times at least Thirty Pins in her presence, and had most fierce and violent Fitts upon them.” Margaret Arnold soon became convinced that something supernatural was causing the girls' afflictions, as well as believed the girls' allegations that bees and flies forced pins and nails into their mouths.

While the children continued their fits and hallucinations at their aunt's house, an ominous event occurred when an unnamed, “…daughter being recovered out of her Fitts, declared, That Amy Duny had been with her and that she tempted her to Drown her self; and to cut her Throat, or otherwise to Destroy her self.” These visions could be seen as signs of severe stress and possible mental illness, as the child affirmed her belief that spectral images were directing her to commit suicide.

The trial itself occurred on March 10, 1662. By then, the afflictions had spread to three other girls, neighbors of the Pacys: Ann Durrant (probably between the ages of 16-21), Jane Bocking (14 years old), and Susan Chandler (18 years old). Deborah Pacy and Jane Bocking were too ill to attend the trial. Though Elizabeth, Ann, and Susan did not testify (family members spoke for them), they were present and affected the courtroom atmosphere. The three arrived…

| ...in reasonable good condition: But that Morning they came into the Hall to give Instructions for the drawing of their Bills of Indictments, the Three Persons fell into strange and violent fits, screeking out in a most sad manner, so that they could not in any wise give any Instructions in the Court who were the Cause of their Distemper. And although they did after some certain space recover out of their fits, yet they were every one of them struck Dumb, so that none of them could speak neither at that time, nor during the Assizes until the Conviction of the supposed Witches. |

| The trial opened with the deposition of Dorothy Durrant. Her statement chronicled old and unprovable events. Durrant did not explain why she had waited several years to accuse Denny. She alleged Amy Denny of bewitching and eventually murdering her ten-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, four years earlier. She also testified that although her infant son, William, suffered similar afflictions, Dr. Jacobs, a physician from Yarmouth, rescued him by recommending the use of counter-magic. Dr. Jacobs told Dorothy to hang William's blanket over the fireplace and to burn anything found in it. When she took it down at night, a large toad fell out, which a boy in the house quickly caught. As he held it over the fire with tongs, the toad exploded with a flash of light. |

| Durrant also testified that the next day, a relative of Amy Denny told her that Denny had recently suffered serious burns all over her body. According to Durrant's deposition, when she visited Denny, the burned woman cursed her and predicted that Durrant would outlive some of her children and be forced to live on crutches. |

| Her predictions soon proved accurate. Durrant's daughter, Elizabeth, soon fell seriously ill, and after seeing Amy Denny's specter, died. After Elizabeth's death, Dorothy Durrant became crippled in both her legs. Judge Hale, attempting to find a natural explanation for the affliction, asked her if the lameness was due to “… the Custom of Women.” Durrant rejected this possibility. Forced to use a crutches for over three years, she threw these away, supposedly cured, when she heard Denny and Cullender pronounced guilty. |

| The most dramatic evidence at the trial was the presence and actions of the children. Elizabeth Pacy created quite a scene, as she: |

| …could not speak one Word all the time, and for the most part she remained as one wholly senseless as one in a deep Sleep, and could move no part of her body, and all the Motion of Life that appeared in her was, that as she lay upon Cushions in the Court upon her back, her stomack and belly by the drawing of her breath, would arise to a great height: and after the said Elizabeth had lain a long time on the Table in the Court, she came a little to her self and sate up, but could neither see nor speak…, by the direction of the Judg, Amy Duny was privately brought to Elizabeth Pacy, and she touched her hand; whereupon the Child without so much as seeing her, for her Eyes were closed all the while, suddenly leaped up, and catched Amy Duny by the hand, and afterwards by the face; and with her nails scratched her till blood came, and would by no means leave her till she was taken from her, and afterwards the Child would still be pressing towards her, and making signs of anger conceived against her. |

After these dramatic events, parents of afflicted children outside the Pacy home testified. They were Edmund Durrant, father of Ann, apparently no relation to Dorothy; Diane Bocking, mother of Jane; and Robert and Mary Chandler, parents of Susan. They swore that their children suffered afflictions similar as to those of the Pacy children, specifically, fit, seeing spectral images, and vomiting crooked pins. They brought to the court several pins as evidence. In a deposition strikingly similar to that of Samuel Pacy, Edmund Durrant, about who nothing is known other than his deposition, described the afflictions of his daughter, Ann:

| …That he also lived in the said, Town of Leystoff, and that the said Rose Cullender, about the latter end of November last, came into this Deponents House to buy some Herrings of his Wife, but being denyed by her, the said Rose returned in a discontented manner; and upon the first of December after, his Daughter Ann Durent was very sorely Afflicted in her Stomach, and felt great pain, like the pricking of Pins, and then fell into swooning fitts, and after the Recovery from her Fitts, she declared, That she had seen the Apparition of the said Rose, who threatned to Torment her. In this manner she continued from the first of December, until this present time of Tryal; having likewise vomited up divers Pins (produced here in Court). This Maid was present in Court, but could not speak to declare her knowledge, but fell into most violent fits when she was brought before Rose Cullender. |

Dr. Thomas Browne, a respected physician who lived relatively close by, testified next. He affirmed that witchcraft existed, specifically mentioning similar events that had occurred in Denmark. Despite mentioning possible medical explanations for the girls' afflictions, namely “the mother,” Browne noted that the Devil could intensify symptoms. Though he believed that the girls were bewitched, he did not specifically state that Denny and Cullender had afflicted them. Browne testified:

| … That the Devil in such cases did work upon the bodies of men and women, upon a natural foundation, [that is] to stir up and excite such humors, super-abounding in their Bodies to a great excess, whereby he did in an extraordinary manner afflict them with such distempers as their bodies were most subject to, as particularly appeared in these children; for he conceived, that these swooning fits were natural, and nothing else but that they call the Mother, but only heightened to a great excess by the subtlety of the devil, cooperating with the malice of these which we term witches, at whose instance he doth these villanies. |

After Browne's testimony, the court carried out several experiments to test the accused witches and their accusers. In contrast to the Mary Glover case, no burning occurred to test the hands for insensibility. Here, the fists of the girls, while afflicted, remained tightly closed, “…as yet the strongest Man in the Court could not force them open; yet by the least touch of one of the supposed Witches, Rose Cullender by Name, they would suddenly shriek out opening their hands, which accident would not happen by the touch of any other person.”

Three respected members of the aristocracy, Lord Charles Cornwallis, a member of Parliament in attendance as a county magistrate, Sir Edmund Bacon, a justice of the peace for the county, and Sir John Keeling (who became Chief Justice of the King's Bench three years after the trial, to be succeeded by Hale in May 1671), one of the three “serjeants,” a post secondary to the judge, tested Elizabeth next. While they supervised, a blindfolded Elizabeth Pacy touched Amy Denny and another woman. When Elizabeth reacted similarly to both women, “…the Gentlemen returned, openly protesting, that they did believe the whole transaction of this business was a meer Imposture.” Samuel Pacy replied “…That possibly the Maid might be deceived by a suspicion that the Witch touched her when she did not.”

Though Pacy's explanation for the test result helped convince the jury of Denny's guilt, other factors also played a role. As the author of A Tryal of Witches acknowledged, many people believed that these girls were not capable of “counterfeiting”:

| It is not possible that any should counterfeit such Distempers, being accompanied with such various Circumstances, much less Children; and for so long time, and yet undiscovered by their Parents and Relations: For no man can suppose that they should all Conspire together, (being out of several families, and as they Affirm, no way related one to the other, and scarce of familiar acquaintance) to do an Act of this nature whereby no benefit or advantage could redound to any of the Parties, but a guilty Conscience for Perjuring themselves in taking the Lives of two poor simple Women away, and there appears no Malice in the Case. For the Prisoners did scarce so much as Object it. |

Depositions by John Soan, Robert Sherringham and Nicholas Pacy (Samuel's father or brother), followed. Significantly, all had civil suits against a John Denny during the 1640's and 1650's. By the time of the trial, Ann Denny's husband, John, was deceased. As there were two John Dennys in Lowestoft at this time, with dozens of civil cases against one or both men, it is impossible to prove that this was the same John Denny.

John Soan accused Rose Cullender of bewitching his three carts, making them unusable for a day. Robert Sherringham blamed her for the loss of four horses and several cows and pigs, as well as his lameness and his suffering a “…great Number of Lice of extraordinary bigness.” Following their testimony, the wife of Amy Denny's landlord, Ann Sandeswell, deposed that Denny complained that her chimney might collapse, which it did a short time later. Additional testimony by Ann concerning the loss of geese and fish ended the depositions.

After these witnesses spoke, Hale had the opportunity to verbally review the evidence for the jury, which he had done in past cases. He did not recapitulate in this case, “… least by so doing he should wrong the Evidence on the one side or on the other.” Instead, according to the writer of A Tryal of Witches, Hale instructed the jury:

| …That they had Two things to enquire after. First, Whether or no these Children were Bewitched? Secondly, Whether the Prisoners at the Bar were Guilty of it? |

| That there were such Creatures as Witches he made no doubt at all; for First the scriptures had affirmed so much. Secondly, The wisdom of all Nations had provided Laws against such Persons, which is an Argument of their confidence of such a Crime…For to condemn the innocent and to let the guilty go were both an abomination to the Lord. |

| The jury took half an hour to convict both women. The spectacle of a tormented eleven-year-old girl fiercely scratching a stereotypical witch, coupled with a great deal of circumstantial evidence, appears to have convinced the jury. The men of the jury, none of whose identity is known, condemned the women to their deaths. |

What generates special interest and significance in the 1662 trial at Bury St. Edmunds is the personal integrity, intellectual acumen, and professional achievements of some of the main participants. Renowned and respected even to this day, Sir Matthew Hale, Chief Baron of the Exchequer, presided over the trial, and Dr. Thomas Browne, knighted 1671, a celebrated author and physician, testified. Both were known for their incorruptibility and tolerance, qualities that undoubtedly helped them to not only survive, but also to prosper during these turbulent times in English history.

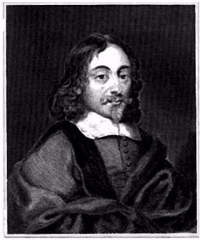

Sir Thomas Browne, a resident of nearby Nottingham, was at the height of his career in 1662. The author of a half dozen major works, his eclectic interests ranged from his candid personal views on religion as a physician (Religio Medici, 1643), to natural history (Pseudodoxia Epidemica, 1646) to ancient funeral rites (Hydriotaphia, 1658). At times skeptical, anti-dogmatic, mystical, erudite, witty, moderate, and curious, Browne and his works had many admirers. Though he dabbled with some scientific experimentation (both he and Hale wrote about magnetism, for instance), Browne, like Hale, also firmly believed in Satan and witchcraft. He believed evil was a part of God's universe, and to doubt the existence of witchcraft opened the door to atheism. Two decades before the trial, in probably his greatest work, Religio Medici (1643), Browne had written:

| It is a riddle to me, how this story of oracles hath not wormed out of the world that doubtful conceit of spirits and witches; how so many learned heads should so far forget their metaphysics, and destroy the ladder and scale of creatures, as to question the existence of spirits. For my part, I have ever believed, and do now know, that there are witches: they that doubt of these, do not only deny them, but spirits; and are obliquely, and upon consequence a sort not of infidels, but atheists. |

Sir Thomas Browne Sir Thomas Browne |

Sir Matthew Hale, four years Browne's junior, also wrote prodigiously. Unlike Browne, Hale chiefly wrote for his own edification and enjoyment. Although he published only a few works, his posthumous History of the Common Law of England (1713) and Histroia placitorum coronae (1726) were highly regarded for centuries. Principally interested in religion and the law, Hale, like Browne, commented on natural history and the relationship between Christianity and reason. Both men typified the culture of the Oxford-educated, successful, well read, and well-respected Englishman at the top of his chosen profession.

Sir Matthew Hale

Sir Matthew HaleDr. Browne of Norwich appears in only one paragraph of A Tryal of Witches, at the Assizes held at Bury St. Edmonds. Unfortunately, neither Browne nor Hale was alive at the time of publication to review and possibly refute the pamphlet. Since neither man mentioned the experience at Bury St. Edmunds in any of their voluminous works or personal correspondence, it is impossible to discern their views towards the events.

Sir Matthew Hale and Sir Thomas Browne are examples of highly intelligent people, at the apex of their respected professions, who sincerely believed in witchcraft. Hale probably presided over at least one other witchcraft case that ended with an execution. In England, however, the era in which it was possible to prosecute and execute witches was ending. Educated justices found executing poor, elderly, and “outcast” women based on the testimony of children problematical. As the belief in witches slowly died out, the ability to prosecute them died out even more quickly.

| The real grievance against these men is that they are judged by later legal, medical, and scientific standards, not those of their own era. Edmund Gosse, a biographer of Browne, characterized his participation in the trial, “…the most culpable and the most stupid action of this life…Among the most appalling stories of witch-trials, none was more shocking, none more inexcusable than that which resulted in the hanging of Amy Duny and Rose Cullender.” Hale's biographer, Edmund Heward, found the omitting the summary of evidence at the end of the trial a “sign of weakness” and alleged that Hale's behavior “…indicates the credulity and superstition which mingled with his religious beliefs.” |

In 1693, when Reverend Cotton Mather published his Wonders of the Invisible World, he enclosed a chapter entitled “A Modern Instance of Witches: Discovered and Condemned in a Trial Before That Celebrated Judge, Sir Mathew Hale.” Mather begins, “It may cast some Light upon the Dark things now in America, if we just give a glance upon the like things happening in Europe. We may see the Witchcrafts here most exactly resemble the Witchcrafts there.” After stating that the trial was “…much considered by the Judges of New England,” Mather summarized A Tryal of Witches in the next nine pages of his book.

Cotton Mather, like Browne in his testimony at Bury St. Edmunds, believed that the Devil could “stir up and excite humors,” especially in children and females. Describing the afflictions of Mercy Short, whose possession occurred within a year after the Salem trials, Cotton Mather wrote Another Brand Pluckt Out of the Burning. Emulating Browne's testimony, Cotton Mather wrote:

| That the Evil Angels do often take Advantage from Natural Distempers in the Children of Men to annoy them with such further Mischiefs as we call preternatural. The Malignant Vapours and Humours of our Diseased Bodies may be used by Devils, thereinto insinuating as engine of the Execution of their Malice upon those Bodies; and perhaps for this reason one Sex may suffer more Troubles of the kinds from the Invisible World than the other, as well as for that reason for which the Old Serpent made where he did his first Address. |

| Unfortunately, in terms of what soon would unfold at Salem, Hale's judgment and Browne's opinions continued to influence events even after their deaths. Though witchcraft beliefs were dying out, the impact of Bury St. Edmunds remained. As historian James Sharpe has written, “The Bury St Edmunds trial of 1662 demonstrated how, even in the face of a court willing to entertain the possibility of deception, and anxious to subject a witchcraft accusation to as many of the known tests and methods of proving witchcraft as possible, the accepted standards of proofs in witchcraft trials were still difficult to reject.” |

The Sir Thomas Browne statue in Norwich The Sir Thomas Browne statue in Norwich

|